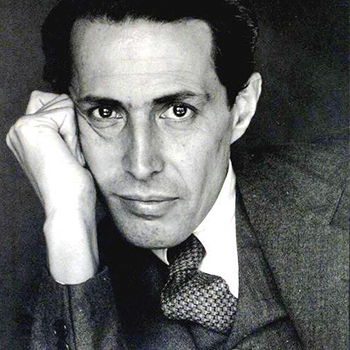

Mérida, Carlos – Guatemala-Mexico

1891-1984 | Latin American Art

Born into a middle-class family in the city of Quetzaltenango, Guatemala, in 1891. His father, a lawyer, was of Maya-Quiché (k’iche’) heritage, and his mother, a teacher, was Spanish.

He started his music training at a young age but was soon forced to give up this discipline due to hearing problems (he suffered from otosclerosis, a disease that eventually left him deaf). With his greatest passion frustrated, Mérida continued to develop his skills and training in plastic arts, his other interest from childhood. He studied painting at the Institute of Arts and Crafts of Guatemala. Here he was to meet the painter Carlos Valenti, whom he befriended, accompanying him on a trip to Paris in 1912.

After living through his friend’s tragic suicide just four months after his arrival in France, Mérida was devastated and left the country. He set off on a journey around Europe, visiting countries such as Spain, where he took geometric design classes at Anglada Camarasa’s academy on the recommendation of Picasso himself. He later returned to Paris.

He went back to Guatemala in 1914, with the First World War on the verge of breaking out in Europe. He started to put on solo exhibitions shortly after arriving, and became well established in Guatemala and internationally.

In 1919, coinciding with the end of the Mexican Revolution, Mérida travelled to Mexico and settled there. This was to have a marked effect on his work and the history of Mexican art alike.

Mérida was to travel repeatedly to New York and Paris. More specifically, he returned to the European continent in 1927, during which he was linked to the Surrealist movement.

Carlos Mérida (Guatemala, 1891 – Mexico, 1984) began his artistic training in his country of birth and soon travelled to Europe in 1912, where he spent time in Spain and France. With regard to the European artistic avant-garde he was interested in questioning established canons. Of all the movements, he was particularly interested in Cubism and abstract art, which once again focus on the artistic object and on formal and aesthetic topics, or in other words, on the essence of the painting.

Between 1915 and 1917, Mérida’s work focused on depicting scenes of daily life and local tradition, in tune with the work of other artists and contemporaries who were also his friends. They came together and based their work on the idea of a common national character, which Mérida would later call the “pro-indigenous movement”. During this period, predominant themes were depictions of indigenous women wearing traditional dress and carrying their children; or representations of indigenous traditions like offering corn or allegories in which women were also the protagonists.

In 1922 Mérida worked as Diego Ribera’s assistant on the latter’s mural Creation in the Bolívar Amphitheatre at the Former College of San Ildefonso. Despite these beginnings in the art world, he would soon detach himself from the concept of national art proposed by the Mexican School of Painting to commit to a language of local references that in turn were based on international art. He therefore became part of the so-called Breakaway Generation, which also included artists like Rufino Tamayo and José Luis Cuevas.

Mérida proposed a new national art linked to the pre-Columbian heritage and formalistic theories of art; a type of art based on plastic and formal themes, far from narrativity.

He travelled to Paris again in 1927. During this second stay, his language leaned towards lyrical abstraction, with references to indigenous culture being strongly present. Continuing with the simplification of his language, his line softened and his compositions became more dynamic. In his works from the 1930s and 1940s we can see the influence that modern European painting had on him, especially Surrealism, with which he was linked, and the work of artists like Miró, Klee, Kandinsky and Picasso. However, Mérida was to maintain his pure essence of the Americas and his search for art that reflected national identity.

Between the 1950s and 1960s Mérida worked on art with an architectural vision, meaning that he conceived it as an integral part of an architectural whole (which he calls “integrated art”). Geometry returns to his work, allowing him to transform his Indian figures and integrate them into architecture, making monumental creations, just like the architecture itself. His language maintains its lines and textures.

In the 1970s he reached his highest level of geometrisation, with even more rectilinear forms, but preserving the vitality of colour (reds, blues, browns, turquoises, oranges).

His language is based on the combination of figurative pre-Columbian elements with abstract modern language, which combines muralism, Cubism, Surrealism and the Mesoamerican artistic tradition.

Throughout his career Carlos Mérida employed a wide variety of techniques in his work, including oil paint, watercolour, gouache, pencil, parchment, plastic, glass, ceramics and tempera (mural).

Silvia Sánchez Ruiz

Curator

ESPINOSA CAMPOS, Eduardo. “Notas sobre la relación de Carlos Mérida con la música y la danza”. En: Entre acordes y pinceladas : La música mexicana en imágenes pictóricas. Coord.: ZAMORANO NAVARRO, Beatriz. ADDENA, N14, 2006. Available at: https://docplayer.es/14237035-Entre-acordes-y-pinceldas.html [date consulted: 10/12/2022]

FERNÁNDEZ ORDÓÑEZ, Rodrigo. “Carlos Mérida a mano alzada” [online]. UFM. Available at: https://educacion.ufm.edu/carlos_merida_a_mano_alzada/ [date consulted: 10/12/2022]

MÉRIDA, Carlos. “Abstracción y Americanismo” (México, 1957). Available at: https://icaa.mfah.org/s/es/item/868536#?c=&m=&s=&cv=1&xywh=99%2C299%2C1462%2C818 [date consulted: 13/12/2022]

SHEEHY, William. “Carlos Mérida” [en línea]. En: Latin American Masters. Available at: https://www.latinamericanmasters.com/es/noticias/carlos-merida [date consulted: 22/10/2022]